Can politics be kept separate from religion? Should we pledge allegiance to one nation under God, or is allegiance to God irrelevant to the allegiance we pledge to our country? And, if God is irrelevant, what does it say about what we’re pledging? These questions, as relevant as they are to natives of the United States, are especially relevant to the natives of France, a nation that still lives under the shadow of the anti-Christian revolution which ripped that nation apart in 1789.

This was evident in the reaction to the surprise success of a new film inspired by France’s Catholic heritage, Sacré Coeur: Son règne n’a pas de fin (Sacred Heart: His Reign Has No End), which was released in cinemas in September. Within the first few weeks of its release, almost 300,000 people had flocked to see it.

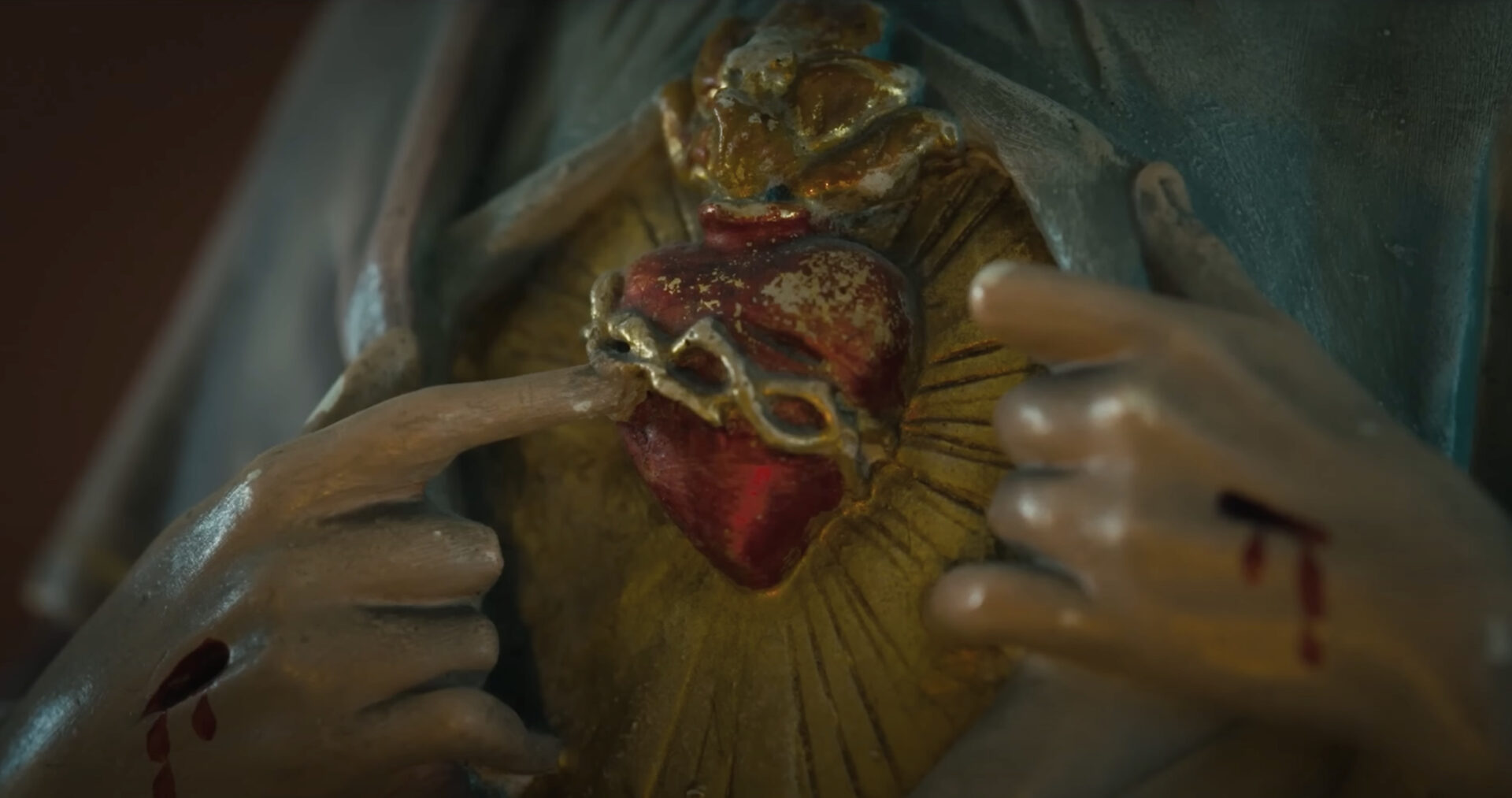

Produced by Steven Gunnell, a convert to the Faith, and his wife Sabrina, Sacré Coeur is a docu-drama focusing on the mystical visions of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque and the widespread devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus which her visions inspired among the faithful around the world. Costing a modest $600,000 to make, the film seems set to break all box office records for a documentary.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

Unsurprisingly, the success of Sacré Coeur has proven highly controversial in the volatile political atmosphere of contemporary France. It might even be said that the film’s vision of Heaven led to all hell breaking loose, especially in the vitriolic response of those who support laïcité, France’s strictly enforced state secularism. Posters advertising the film were banned by the Paris public transport system and by the state rail operator on the grounds that they were “confessional and proselytizing” and “incompatible with the principle of public service neutrality.” Steven Gunnell highlighted the hypocrisy of those seeking to ban advertising of the film, stating that films with an anti-Christian message were advertised freely in public spaces.

In similar secularist fashion, the mayor of Marseille banned the film an hour before it was due to open at the Château de La Buzine, the city’s principal cultural center, arguing that “a public facility cannot host screenings of a religious nature.” Fighting back, the filmmakers won a court injunction forcing the mayor to permit the screening of the film in Marseilles. “The mayor of Marseille committed a serious and manifestly unlawful infringement of freedom of expression, freedom of creation, and freedom of artistic distribution,” the judge ruled. Agreeing with the judge’s verdict, Hubert de Torcy, head of SAJE, the film’s distributors, described the ban as incomprehensible because “the film’s subject is part of French history and French culture.”

body .ns-ctt{display:block;position:relative;background:#fd9f01;margin:30px auto;padding:20px 20px 20px 15px;color:#fff;text-decoration:none!important;box-shadow:none!important;-webkit-box-shadow:none!important;-moz-box-shadow:none!important;border:none;border-left:5px solid #fd9f01}body .ns-ctt:hover{color:#fff}body .ns-ctt:visited{color:#fff}body .ns-ctt *{pointer-events:none}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-tweet{display:block;font-size:18px;line-height:27px;margin-bottom:10px}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-cta-container{display:block;overflow:hidden}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-cta{float:right}body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-cta-left .ns-ctt-cta{float:left}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-cta-text{font-size:16px;line-height:16px;vertical-align:middle}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-cta-icon{margin-left:10px;display:inline-block;vertical-align:middle}body .ns-ctt .ns-ctt-cta-icon svg{vertical-align:middle;height:18px}body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple{background:0 0;padding:10px 0 10px 20px;color:inherit}body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple-alt{background:#f9f9f9;padding:20px;color:#404040}body .ns-ctt:hover::before{content:”;position:absolute;top:0px;bottom:0px;left:-5px;width:5px;background:rgba(0,0,0,0.25);}body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple .ns-ctt-cta,body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple-alt .ns-ctt-cta{color:#fd9f01}body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple-alt:hover .ns-ctt-cta,body .ns-ctt.ns-ctt-simple:hover .ns-ctt-cta{filter:brightness(75%)}The mayor of Marseille banned the film an hour before it was due to open at the Château de La Buzine, the city’s principal cultural center, arguing that “a public facility cannot host screenings of a religious nature.”Tweet This

Without wishing to beg to differ, or to play devil’s advocate, Monsieur de Torcy was being somewhat naïve. It was precisely because the subject of the film was part of French history and culture that the secular fundamentalists were seeking to ban it. The revolutionary founding fathers of the secularist French Republic sought to wipe out all memory of the nation’s profoundly Christian past.

They executed and persecuted Christians, guillotining and exterminating hundreds of thousands of the nation’s Catholic population and forcing countless more into exile. They even banned the Christian calendar, replacing the birth of Christ as the turning point of history with the date of the Revolution itself. Like Hitler’s “Thousand Year Reich,” which only lasted 12 ignominious years, the French Revolutionary calendar also lasted 12 equally ignominious years, from 1793-1805.

As for devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, it inspired those who resisted the secular fundamentalist madness. An image of the Sacred Heart was the emblem worn close to the heroic hearts of the peasants of the Vendée who rose up against the Revolution’s pogrom against the Catholics of France. It was also the inspiration and emblem of the Catholics who opposed and ultimately defeated the proto-communist Communards who established the Paris Commune in 1871. In commemoration and celebration of the defeat of the Commune, and as an act of thanksgiving to God for delivering France from the enemies of the Faith, the great Sacré Coeur basilica of Montmartre was built in honor of the Sacred Heart.

Yes indeed, Monsieur de Torcy, devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is very much an integral part of French history and culture, and this is precisely the reason why the film attracted so much hostility from those who sympathize with the butchers of the French Revolution.

More surprising, perhaps, is the opposition to the film expressed by neo-liberal Catholics in an open letter published in La Croix, a Catholic daily newspaper, which expressed alarm at the success of the film because it illustrated “the growing normalisation of far-right ideas within the Christian community.” Even more shocking for these “progressive” Catholics was that “the Sacred Heart of Jesus is being put at the service of a political agenda whose obsession is the reaffirmation of France’s Christian identity.”

Perhaps these self-styled “modern” Catholics would consider that the heroes of the Vendée had “far-right ideas.” It is, in any event, revealing that those seeking to reaffirm France’s Christian identity are seen by these neo-liberal Catholics to be pursuing a political agenda. Is the desire for the conversion of one’s nation to the Sacred Heart of Jesus a far-right “obsession”? Is doing something practical to win converts to the Faith an “obsession,” or is it something commanded of us by Christ? What faux Catholics call “obsession,” real Catholics call evangelization.

Sacré Coeur has been seen by hundreds of thousands of French theatergoers. For this great example of Catholic evangelization, we should give praise to God in the hope that it will lead many to Jesus’ Sacred Heart. As for those who use their lips to utter the curse of Caesar or to bestow the kiss of Judas, may we pray that their hearts might change and that the Sacred Heart of Jesus might have mercy on them.